|

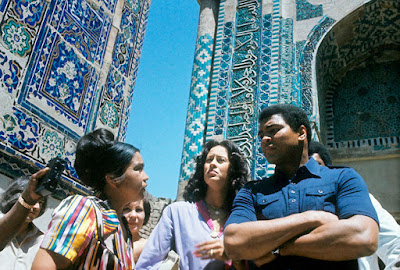

| Muhammad Ali and Veronica Porsche wearing traditional Uzbek skull caps |

It was a surprise for many in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1978, when Communist authorities decided to roll out a red carpet for a celebrated and self-avowed Muslim.

That year, legendary boxer, Muhammad Ali, who died on June 3, was invited to visit the Soviet Union. With two years to go before the Moscow Olympics, the Communist Party Central Committee apparently wanted to reap some good PR from the living legend’s trip.

Ali flew into Moscow with his retinue, which included training staff, lawyers and his then-wife Veronica Porsche. The morning after his arrival, the boxer caused something of a minor diplomatic incident by taking advantage of a clear early summer dawn to go on a jog through the middle of the city and into Red Square. The sight of an Ali in shorts trying to do a circuit around Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin’s mausoleum startled Soviet authorities.

On June 15, after a three-day stint in Moscow, Ali traveled onward to Uzbekistan. The republic was of particular interest to the boxer as an important site of Islamic history and culture.

Nuriddinmahsum Usmanov, now the imam at a mosque in the Kashkadarya region, recalled seeing the news of Ali’s arrival on television. Back then, Usmanov was a student in Bukhara at the only active madrassa allowed in Uzbekistan at the time.

“We saw his arrival on Uzbek television and we were stunned that he was called Muhammad Ali,” Usmanov told EurasiaNet.org. “We were amazed, since it was the Soviet times and Islam was forbidden, and here is this man with a Muslim name.”

> |

| Muhammad Ali at Shah-i-Zindar, Samarkand |

A delegation turned out to meet Ali as he got off the plane that brought him to Tashkent from Moscow. Officials thought it would be a good idea to include Rufat Riskiyev, a local hero who won silver for the Soviet Union as a middleweight boxer at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, in the welcoming committee. The encounter went poorly, however.

“We were taken aback that when they introduced our Rufat to him, Muhammad Ali didn’t pay him any attention. Riskiyev took it very badly and failed to turn up at later events,” said Hurshid Dustmuhammad, a veteran Uzbek journalist who covered Ali’s visit.

According to one account relayed by the Uz24 news website, Ali compounded the insult by answering when asked whether he knew Riskiyev: “No, I do not know amateurs.”

Speaking to EurasiaNet.org, Riskiyev offered a somewhat different version of events, perhaps finally getting one over Ali.

“It was me that didn’t recognize him at the time! So I didn’t recognize him, what of it? And then we met in the boxing hall at a sporting club … and he recognized me immediately. So I wasn’t offended at all,” Riskiyev said. “When I heard he had died, it was like somebody had jabbed a needle in my heart. He was the greatest boxer of the 20th century.”

|

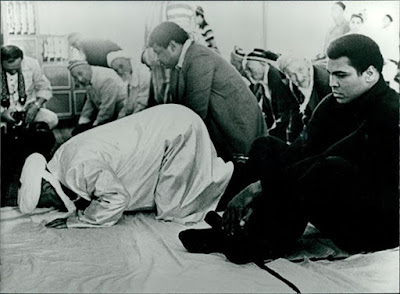

| Muhammad Ali at an Uzbek mosque |

At every event he attended, Ali was greeted with tables creaking under the weight of fruit, candy, wine, brandy and, inevitably, plov, to which he apparently took quite a liking. On his return to Moscow, Ali claimed he had piled on four kilograms during his stay in Uzbekistan.

Uzbek officials clearly had a poor grasp of how to keep their guest happy.

“At the press conference organized for Ali’s arrival, the chairman of the Uzbek State Sports Committee [Mirza] Ibragimov spoke about all the achievements of Uzbek athletes. Muhammad Ali paid no attention and instead picked at the grapes on the table,” Dustmuhammad said.

Ali was similarly unimpressed by a tour of Tashkent’s Lenin Museum. “He didn’t listen to the guide and often stood about 10 meters away from him,” Dustmuhammad said.

When he walked the streets of Tashkent, however, Ali suddenly came alive. “If he saw some strong young guys, he would suddenly start shadow-boxing. It was really strange for us and we couldn’t understand what he was doing. But then it dawned on us that he was putting on a show,” Dustmuhammad recalled. “We were Soviet people with stiff manners, and he was an American and relaxed.”

|

| Muhammad Ali at an Uzbek banquet |

The highlight of the stay in Central Asia for Ali, though, was a trip to the city of Samarkand, where he paid tribute at the mausoleum of 9th century Islamic scholar Imam al-Bukhari and visited an observatory built by 15th century astronomer Ulugbek. While in the city, he was taken to a mosque and joined in with prayers — an event memorialized in a photograph showing the boxer alongside a dozen or so other congregants.

A piece on Ali’s visit to the Soviet Union by the Russia-based Just Boxing website includes a detail on an alleged faux pas he is said to have committed. At a mosque, Ali was given a robe embroidered with golden thread. “For a Muslim, a robe like this is something of great value. To the surprise of faithful Uzbeks, when he prepared to leave, he used the robe to wrap up some dishes that he had been given and with a sweeping gesture threw the bundle into the trunk of a Volga [automobile],” the website wrote.

As with so many other similarly colorful stories, sorting fact from fiction is all but impossible.

Official Soviet news organs predictably milked Ali’s tour for all it was worth. New York-based Novosti news agency reporter Genrikh Borovik approvingly cited a number of Ali quotes purportedly culled from US coverage of the trip. “I was struck by how many races and nationalities there are there. There are not less than 100 nationalities and they live in harmony,” Ali was cited as saying by Borovik. “No one hinders religious belief there. Religious Jews attend the synagogues. The Muslims have mosques.”

But following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Ali would drastically change his views and threw himself actively behind the campaign to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games. The United States was among the nations that opted not to compete in Moscow.

|

| Muhammad Ali meets young, Soviet boxers |

“When I heard about his death, I posted a photo from the archives on my Facebook page, showing Muhammad Ali standing next to his wife wearing an Uzbek robe and a tyubeteika [skull cap]. His wife was wearing a tyubeteika too,” Dustmuhammad said. “Whatever his qualities may have been, may Allah take in his soul.”

Related posts:

Sidney Jackson - An American Boxer in Uzbekistan

Duke Ellington's Kabul Gig 1963

Langston Hughes: An African American Writer in Central Asia in the 1930s

Uzbekistan Still Mourns a Football Generation Lost to Air Crash - Part #1