|

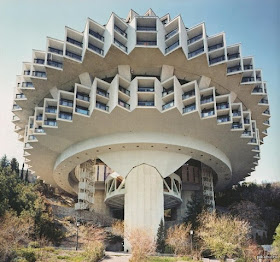

| Druzhba, a Constructivist masterpiece on the Crimean shore that sparked rumours that a flying saucer had landed |

As author Omidi writes, "sanatoriums were originally conceived in the 1920s, and afforded workers a place to holiday, courtesy of a state-funded voucher system.

At their peak they were visited by millions of citizens across the USSR every year. A combination of medical institution and spa, the era’s sanatoriums are among the most innovative buildings of their time".

Although aesthetically diverse, Soviet utopian values permeated every aspect: western holidays were perceived as decadent. By contrast, sanatorium breaks were intended to edify and strengthen visitors – health professionals carefully monitored guests throughout their stay, so they could return to work with renewed vigour. Certain sanatoriums became known for their specialist treatments, such as crude oil baths and radon water douches.

Visiting a Soviet-era sanatorium is like stepping back in time. Vestiges of another age linger all around — in fragments of decades-old wallpaper stubbornly clinging to walls, or colourful mosaics glorifying the Soviet worker.

Soviet-era sanatoriums are among the most innovative, and sometimes most ornamental, buildings of their time – from Kyrgyzstan’s Aurora, designed in the shape of a ship, to Druzhba, a Constructivist masterpiece on the Crimean shore that sparked rumours that a flying saucer had landed.

|

| Kyrgyzstan’s Aurora sanatorium, designed in the shape of a ship |

Sprinkled across the post-Soviet landscape, they survive in varying states of decay, with relatively few still in operation. But at their peak, these sanatoriums were visited by millions of citizens across the USSR each year, courtesy of the state.

The 1922 Labour Code prescribed two weeks’ holiday a year for many workers and under Joseph Stalin the "right to rest" was enshrined in the 1936 constitution for all citizens of the USSR.

In line with Stalin’s First and Second Five-Year Plans, writes Johanna Geisler in The Soviet Sanatorium: Medicine, Nature and Mass Culture in Sochi, 1917–1991, rapid development of the industry meant that by 1939, 1,828 new sanatoriums with 239,000 beds had been built.

It was against this backdrop that the sanatorium holiday was born. A cross between medical institution and spa, the sanatorium formed an integral part of the Soviet political and social apparatus. They were designed in opposition to the decadence of European spa towns such as Baden-Baden or Karlovy Vary, as well as to the west’s bourgeois consumer practices. Every detail of sanatorium life, from architecture to entertainment, was intended to edify workers while encouraging communion with other guests and with nature.

|

| Ultraviolet light-emitting sterilization lamps are placed in the ear, nose or throat to kill bacteria, viruses and fungi |

Soviet holidaymakers would start with a visit to the resident doctor, who would draw up a tailor-made programme of callisthenics, dietary recommendations and treatments.

Traditional therapies such as mineral-water baths were offered alongside more innovative treatments such as electrotherapy. Some sanatoriums provided regional treatments such as grape therapy in Crimea or kumis (mare’s milk) in Central Asia, which is still offered at Jeti-Ögüz sanatorium in Kyrgyzstan today.

The withering of the Soviet Union in 1991 sounded the death knell for the industry, leaving many sanatoriums boarded up and abandoned. Prohibitive maintenance costs coupled with lack of interest in architectural conservation in much of the post-Soviet sphere have done little to change this situation. A number of the sanatoriums still in operation have fallen into disrepair, while others face an uncertain future.

|

| Tskaltubo, central Georgia. Frequented by the Soviet elite and linked by a special train from Moscow |

Speak to any sanatorium doctor today and the word prophylactic inevitably crops up, in a nod to Soviet medicine’s focus on preventative clinical work.

A stay at a sanatorium is still seen as both prevention and cure, with guests seeking treatment for a wide range of illnesses from arthritis to asthma".

Not surprisingly, little is known about sanatoriums outside the post-Soviet sphere.

Given the faint regard for their conservation, Omidi's book aims to introduce sanatorium culture to those to whom it is new, while highlighting the architectural gems of the Soviet era in the hope that they will be protected and restored for future generations.

On an Uzbek Journeys tour to Kyrgyzstan, you will see the famous Jeti-Ögüz sanatorium as well as stroll through the grounds of the Tamga sanatorium, training centre for Soviet cosmonauts and athletes. A visit to an outdoor bath in the mountains around Karakol is also included.

Below are some images from the book of treatments offered today, some of which are quite extraordinary.

Want to buy a copy of this marvellous book? The final image is the book cover with all the details.

Related posts:

Kyrgyzstan: Jety-Oguz and One-of-a-Kind Health Resort

Kyrgyzstan: Monumental Art in the Provinces (to view mosaic panels in Kyrgyz sanatoriums)

Kyrgyzstan's Bus Stops

Back in the USSR: Soviet Roadside Architecture

|

| Forget seaweed baths, it's all about crude oil at the sanatoriums in the Azerbaijani city of Naftalan. The so-called "miracle oil" is said to be excellent for skin and joint conditions |

|

| Salt room, Zaamin sanatorium, Uzbekistan |

|

| High frequency electrotherapy, good for blood pressure and circulation |

| ||

| A man resting by the radon water pool at Khoja Obi Garm sanatorium in Tajikistan |

|

| Klyazma centre, built in 1963 near the Klyazminsky reservoir on the outskirts of Moscow |