Housed in the basement of a building designed by prominent Soviet modernist architect, Richard Vladimirovich Bleze, on prime real estate in the centre of the city, the theatre is under threat.

Many Uzbek Journeys clients attended theatre performances, concerts, film screenings and exhibitions here. They were surprised and delighted by the innovative performances, staging and atmosphere.

The theatre company tours abroad to rave reviews, garnering international awards including the prestigious Prince Claus award for its achievements in the field of culture. Ilkhom has been described as "a tiny, bright and incredibly unlikely beacon of light".

Actor Tyler Polumsky reflected "It’s hard to imagine how the theatre would continue without that space". But there is also something deeper. Actors believe that the squeaky, time-worn planks of the Ilkhom stage are as integral to the theatre as its repertoire, its audience, and its school. "The Ilkhom is years of psychological, spiritual energy swallowed up in that space, in the atmosphere of that building," says Polumsky. "Moving it elsewhere is out of the question, something irreplaceable would be lost".

|

| Scene from "Happy are the Poor" |

During Tashkent's lockdown, Ilkhom has demonstrated its creativity organizing high standard online plays, concerts, book readings all with the aim of defending the theatre as a cultural icon of the city. Despite the harsh impact of quarantine on actors and theatre staff, these performances have been witty, professional and at times profound.

The talk of demolition has been brewing since February. In the article below, managing editor of Global Voices, Filip Noubel, describes the situation in an article published in February 2020. At the end of this article are some suggestions how you can help.

An iconic independent theatre in Uzbekistan's capital is threatened with expulsion, revealing tensions among political and economic elites as Central Asia's most populous country engages in bumpy reforms. As Tashkent changes rapidly, a public campaign is underway to save one of the country's most beloved independent cultural spaces.

From its very beginning, the Ilkhom Theatre in Tashkent distinguished itself as an unusual place. The theatre's name means “inspiration” in Uzbek, and it was founded in 1976 by Mark Weil, an artistic director who managed something quite astonishing: to some extent, he was able to avoid the pervasive censorship of the time.

|

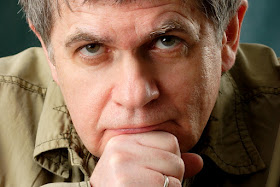

| Mark Weil - actor, director and founder of the Ilkhom theatre. This photo greets the audience as you walk down the stairs to the theatre. |

Under Soviet rule, culture was considered another domain of communist ideology, and its purpose was to support the ruling party's line. In a system without a market economy, operating without state subsidies was close to impossible, but Weil found a way — all while retaining a remarkable degree of independence as an avant-garde art director.

The situation changed significantly when Uzbekistan declared independence in 1991: unfettered capitalism, along with unprecedented freedom of expression, swept the country. Many state supported cultural institutions went out of business. Weil once again worked his magic and was able to raise the profile of the Ilkhom Theatre as an renowned space for experimental drama. The theatre was awarded international prizes and managed to survive economically thanks to a mix of grants, devoted theatregoers, its own café and drama school, and support from overseas.

As Uzbekistan changed its language policy and promoted the use of Uzbek against the previously privileged Russian language, the Ilkhom Theatre also became a rallying point for intellectual Russian speakers, regardless of their ethnicity.

The relative freedom of expression experienced by most post-Soviet states in the 1990s ground to a halt in Uzbekistan after a series of bombings in 1999, and was further curtailed after the 2005 Andijan unrest.

While the Ilkhom Theatre managed to preserve some freedom, a huge blow came on September 7, 2007 when Weil was assassinated. The circumstances of his murder remain murky to this day. While his killers were apprehended, some observers situate their motives in the context of a conservative, predominantly Muslim society. For example Weil's play Imitation of the Koran, based on a poem by the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, provoked controversy in Uzbek society— as did Weil's own homosexuality.

|

| Poster for Imitation of the Koran |

Remarkably, the actors of the Ilkhom Theatre decided to perform on the day after Weil's murder. They argued that “the show must go on,” contributing to yet another legend surrounding the name Ilkhom.

Enter the Bulldozers

A new chapter commenced in Uzbekistan's history when President Islam Karimov, who had ruled uncontested for nearly three decades, died in September 2016 and was succeeded by former Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev. The country rapidly embarked on a programme of political and economic reforms with mixed results. While there has been liberalisation in some areas, corruption, lack of access to justice, and censorship still affect Uzbek society deeply.

The Ilkhom Theatre may have survived censorship and economic upheaval, but now it faces another foe: massive urban redevelopment. The unbridled urbanisation of recent years has destroyed many of the Uzbek capital's landmark buildings from the Soviet period. One example was the demolition of the House of Cinema (Дом Кино) in January 2018, a Soviet-era building which hosted international film festivals. The government justifies these moves as progress, part of a move to transform the capital under the banner of Tashkent City, a US$3 billion mega project that has turned large parts of city centre into a building site.

|

| Tashkent's famous House of Cinema, designed by Rafael Khairutdinov, was demolished in 2018 |

The Ilkhom Theatre occupies part of the ground floor and the basement of a larger building which also houses the Shodlik Palace hotel. On February 7, the new owners of the building, the Olefos Plaza company, sent a letter to the Ilkhom Theatre, informing them to vacate the premises due to reconstruction works.

The theatre had a special agreement with the previous owner guaranteeing a rent free lease until 2023, with an automatic extension of the contract for another ten years. However, that contract was superseded in 2017 when the government took over the building and sold it to the Ofelos Plaza company. Following this announcement, supporters of the theatre as well as its staff launched several online campaigns, including the hashtag #saveilkhom on Facebook and Twitter.

A bilingual website has also been launched to garner local and international support and host petitions. But it seems this is not just an opposition movement. Unusually, one of the voices calling for the preservation of the theatre is that of Saida Mirziyoyeva, daughter of the current president. Mirziyoyeva, who serves as deputy director of the government's foundation for mass media development, wrote the following on February 11:

"I'd like to comment on the situation around the Ilkhom Theater. I myself am a fan of the theater and want to assure everyone that we won't forsake it! Ilkhom is the pride of our cultural life!"

|

| Exterior view of the complex - the Ilkhom theatre is in the smaller building on the left. On the right is a hotel. |

While it seems that Mirziyoyeva's statement might have given the theatre a chance to stay where it has existed since 1976, staff at the theatre remain cautious. According to Deputy Director Irina Bharat, the new plan of the building's owners is to reconstruct the whole premises over a period of two years and add new floors, meaning that: "As we understand, that they will need to dig a pit, meaning that our theatre will be destroyed".

Uzbek documentary photographer and filmmaker Timur Karpov told GlobalVoices that the story was far from over: "She [Mirziyoyeva] as well as her father, are image makers, they need a positive image among the public. Now all depends on how far both sides can go. There is a real chance that Ilkhom can survive, but if the authorities start pressuring the management of the theatre, they will have to give in. They'll need to come to a compromise and find a new building. That whole process will take years".

Ashot Danielyan, a poet and rock musician who organises events at the theatre, believes that the theatre requires formal protection from the state, rather than depending on the whims of the building's owners:

"The only way to save the theatre is to make it untouchable, as a place of historical and cultural significance. “Ilkhom” means inspiration. For me, it's one of the most inspirational places in Tashkent. Since 2007, it's where we've been organising the country's only festival of rock music. Without this theatre, the entire alternative music scene could disappear; for many young bands, it's the only available venue for performances".

|

| At a rally to try to save Ilkhom, this young girl holds a poster"Tashkent Needs the Ilkhom Theatre". Image: Rustam Khusanov |

How can you support Ilkhom?

Many prominent directors, actors and singers from around the world have written to the Uzbek government urging it to bestow the status of cultural and intangible heritage on the theatre. Embassies in Tashkent continue to provide support for Ilkhom's online activities during lockdwon.

At the time of writing - June 2020 - it is unclear what will happen.

As ordinary people we can show our support by adding our names to the #SaveIlkhom website, by reposting this article and, if there is an Uzbek embassy or consulate where you live (see list) writing and urging the government to save this cultural heritage. Without the Ilkhom theatre, Tashkent will lose its soul.

Related posts:

Tashkent: A Night at the Opera

Uzbekistan as Film Location

Tashkent's Soviet Buildings

Seismic Modernism - Architecture and Housing in Soviet Tashkent