Three Bishkek-based artists/activists have started a remarkable online marketplace for Central Asian contemporary art. The article below, written by the initiators, was first published on TransitoryWhite on 14 May 2020. Through this marketplace I have been able to buy pieces by some of Central Asia's best known artists as well as by emerging artists.

At the bottom I explain how, with little Russian, I have been able to do so. Do please read the article, perhaps over a cup of green tea, to understand the aims of this innovative bazaar.

PULLING OURSELVES OUT OF THE SWAMP

By Meder Akhmetov, Darina Manasbek, Philipp Reichmuth

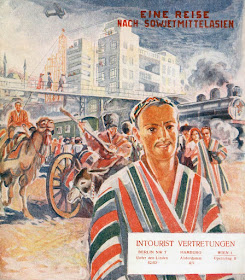

|

| Valery Ruppel, "New Forms of Tulips or Political Botanic, dedicated to the 2005 Kyrgyz Tulip Revolution. |

For Central Asian artists, the coronavirus lockdowns promised to be a time of dread and survival. However, the time of lockdowns and isolation turned out to be a time charged with emergent power, giving birth to a unique emerging situation.

This is Art Bazaar, a social media experiment with 1000+ participants launched in mid-April and currently run by architect/artist Meder Akhmetov, artist Darina Manasbek, and consultant/activist Philipp Reichmuth. Apart from a social media experiment, it is also a successful informal art market and a means for artists to survive the crisis.

Technically, Art Bazaar is just a closed Facebook group (Художественный базар), modelled on a similar group that emerged two weeks earlier in Moscow. In its function, Art Bazaar is a platform for artists to sell their artworks for low prices.

|

| Saule Suleimenova, “Three Brides”. Plastic bags on a polyethylene base, |

However, what is more important than the pure commerce is the community-building and networking aspect. The crisis threatens to drive many artists into depression and destitution, and for us as moderators of Art Bazaar - in particular for Meder as the original initiator - the plight of our friends and colleagues was a strong personal reason to experiment with new formats.

Art Bazaar operates with a few simple rules, that can be summarized as follows:

1. "Sell three - buy one": if you sold three works, you buy one for yourself from another artist.

2. "Bought one - sell two": make sure that you contribute to the market yourself, and if you have nothing to sell - contribute in some other way.

3. "Sell ten - donate one": if you sold ten works, you donate one of your choice to a joint Art Bazaar collection.

These simple rules encourage participation and redistribution. Young members as well as established artists with international names are contributing, and experimental and conceptual works are sold alongside more traditional fine art. Sometimes coveted works suddenly become accessible for collectors and fellow artists, while sometimes established artists post rare, unusual and experimental works that shows their own exploration of their subjects.

|

| Said Atabekov, Photo “The Veteran of the Ogedei Front |

But the major transformative impact of Art Bazaar comes from its low-price policies. This makes art accessible not only from western passers-by and local elite, but also for the fellow artists and people with moderate income. There are price thresholds of 1000 som ($13) for digital works, 5000 som ($65) for works on paper and 20.000 som ($250) for all other works.

It is very common that artwork is sold for 500 som ($6). Bishkek-based curator Ulan Djaparov contributed a text, reflecting on how this sum represents the crisis management aspect of the group, seeing how it is approximately the sum that a Bishkek family needs to feed itself for a day or two; the manuscript promptly was sold for 500 som.

A new format inevitably raises many questions. For example, the initial participants were all from Kyrgyzstan, but soon Kazakh and Uzbek artists joined, raising questions of money transfer, logistics and currencies - sales are mostly still denominated in Kyrgyz som, even by artists from other countries. The low-price policy has also challenged established notions of how art should be priced and sold.

Apart from traditional formats, such as limited series, artists are experimenting with digital reproductions and selling very large series of up to 500 copies for very low prices to make them accessible. Sometimes this puts artists at odds with the international art market that operates on scarcity, and also with buyers with larger purchasing power, calling for emergent solutions.

The "sell ten - donate one" rule has led to a slowly growing Art Bazaar collection. It now includes works by significant artists such as Valery Ruppel and Marat Raiymkulov (Kyrgyzstan), Elena and Viktor Vorobyev, Said Atabekov and Saule Suleimenova (Kazakhstan) or Dilyara Kaipova (Uzbekistan), as well as many others.

From simple beginnings, the collection has begun to turn to reflect the processes and formats of Central Asian contemporary art since the 2000s. Valery Ruppel donated two sheets from his seminal 2006 "Political Botany of Kyrgyzstan" after the 2005 Tulip Revolution. Saule Suleimenova, contribution was originally intended as her 2016 entry into the annual Bishkek First of April Competition of Contemporary Art, while Marat Rayimkulov’s autobiographical notebooks reflect upon his own trajectory as an artist. As soon as the current COVID-19 restrictions make it possible, it is planned to show the Art Bazaar as an exhibition of its own, at least in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

|

| Dinara Nuger's felted work "Astana" |

The discussions that have begun to emerge within and around Art Bazaar suggest that there is a demand for accessible spaces for discussing art. We see that the community can create self-organized, inclusive art markets for and by artists, whose dynamic does not depend on external actors and gatekeepers. Barriers to participation are deliberately low, moderation is very light, and there are no fees for participation or sales.

Art Bazaar is part of a broader phenomenon of similar groups that have appeared during the COVID-19 crisis. The original was "The Ball and the Cross" (Шар и Крест, after the Chesterton novel), set up April 4 by gallerist Maxim Boxer. It was a hit from the start, transforming the Moscow art market. We (the team behind Art Bazaar) joined this group early, but it seemed to us that the Moscow audience was not particularly interested in the Central Asian artists’ contributions, their subjects and techniques. Practically no Central Asian works were sold and, consequently, their visibility was pretty low.

|

| Nadezhda Kononova-Ruppel's bracelet of lapis lazuli, mother of pearl and malachite |

Out of this frustration, Meder decided to open Art Bazaar as a separate Central Asian group two weeks later (April 16). A similar example of such emergence is "Salt and Pepper" (Соль и Перец), set up April 24 in Ukraine by collectors and gallerist Marat Guelman and Evgeny Karas. It is now the largest such group, with over 10.000 members, and it is distinguished by a 10% transaction fee that goes to the moderators. Art Bazaar has not professionalized to this extent, and it might never do so, seeing that the informality of the bazaar metaphor does not lend itself well to institutionalization.

In comparison, Art Bazaar with its now 1200 members seems modest, but its impact needs to be seen in context. Firstly, Central Asia is a much poorer region, and the more remarkable it is that suddenly there is at least a temporary solution to some problems of survival. Secondly, we see artists empowering themselves in exploring the concept of an artist-driven market for Central Asian contemporary art.

Unlike Moscow or Kiev, in Central Asia a contemporary art market in the Western sense, with galleries, collectors, curators and museums of contemporary art, has never really taken off. Institutions have been eagerly awaited, always been expected just around the corner, sometimes launched. But in spite of the efforts of different generations of art managers, curators and gallery owners, the effort to establish formal institutions has not yet had a broad impact.

|

| Viktoria Tsoy's oil painting "Yurts" |

Maybe this was also because such an art market assumes the power to be in the hand of someone else - gatekeepers, galleries, critics, and other arbiters in the market - and it is a place of formal, sometimes cold relations. Proponents of such an art market often looked with disdain upon the informal artist underground, comparing it with unflattering imagery such as the kitchens of Soviet apartment blocks.

In Art Bazaar, however, the underground has struck back. Social media has allowed turning the market into an informal place, where you can meet, as if for a tea, with established and emerging artists, share artworks without being shy, and earn some money doing it. This informal character seems to matter to the participants, as does the sudden accessibility of the big names; as one participant puts it, "when you’re new, and one of these established artists buys one of your works, you feel like you’re flying" - not a small thing at the times of psychological pressure.

It seems to work - based on what we see and what artists write themselves, we estimate at least 150 transactions over four weeks. This is a small number for an art market, but a revolutionary number in Central Asia.

But Art Bazaar is an emergent phenomenon for us as well, with little theory behind it. We assume that it is precisely this informality that allows Art Bazaar to empower the artists themselves, whom the crisis had put on the edge, forcing them to pull themselves out of the swamp by their own hair. We do not know where this will be going; there is no goal of institutionalization, or even of continued existence after the crisis.

|

| Beibit Asemkul's photograph "Infinity" |

The Central Asian experience is that institutionalization often leads to establishing control, and the privatization of what used to be a common, shared resource by a few powerful players. In a way, rather than be taken over by institutional players and either privatized or turned into a Western-style surplus-generating instrument, it might be preferable to let the bazaar slow down again when the crisis is over. But the solution to this will emerge as well; we believe that much of the impact has been made already.

How to buy:

3. Click the Join the Group button and complete. You will receive a confirmation within 24 hours.

4.

Google Translate is your friend. There should also be a See Translation link within the post.

5. Scroll through the pieces submitted. Sometimes the price can be confusing. Most are listed in Kyrgyz som, exchange rate 1USD = 70 Kyrgyz som (approximately), some in US$. Works are also divided thematically - look at the Popular Topics in Posts on the right-hand side

6. Contact the seller using the Message link at the top of the listing to express your interest directly with the artist and check the price. It is fine to write in English. The artist will reply and also advise the cost of packing and postage. I strongly recommend opting for EMS trackable postage rather than regular airmail.

7. You then pay the artists via Western Union, World Remit, Pay Send etc or direct bank transfer. Once the artist receives the funds, she/he will contact you and advise when the piece is posted.

|

| Askhat Akhmediyarov’s sketch book for the Ayan exhibition in Astana. |